- Joined

- Jul 2, 2024

- Messages

- 849

- Likes

- 2,741

Why Pakistan’s Elite Prefer It Remains Backward?

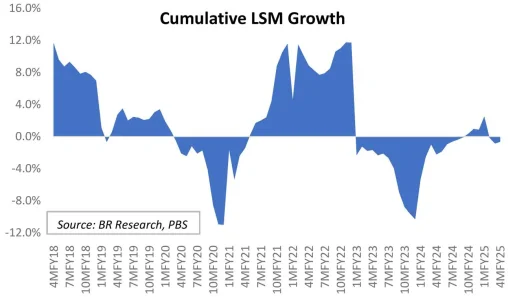

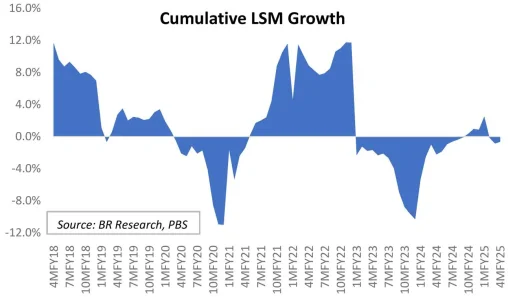

What do you call a nation where large-scale manufacturing (LSM) has been in consistent decline for years? A strong case can be made for labeling it among the lowest of the third-world countries. This is the reality of Pakistan today. Citing data from Business Recorder of Pakistan (December 2024), the situation warrants Pakistan being described as a “begging bowl” nation.

What went wrong with a country that, at the time of its independence from Britain, showed significant promise? Pakistan boasted abundant natural resources, including fertile agricultural land fed by five rivers, perfect for an agro-industrial economy. For its first three decades, the nation experienced moderate progress. Then, in a bid to fuel confrontation with India, Pakistan’s military initiated a process of Islamization. Civilian rule was sidelined, and the military alternated between complete and partial control of the government.

A large portion of national resources, which should have been invested in development and public welfare, were instead funneled to the military. Slogans like capturing Kashmir and Jihad with the mythical Ghazwa-e-Hind—a call to conquer India—were fed to the populace. Mosques and mullahs amplified these narratives, convincing people that prosperity would follow once Pakistan achieved these territorial ambitions. The 1998 nuclear tests only emboldened this delusion, as economic priorities were neglected in favor of military expansion.

Meanwhile, India, facing the above challenges, focused on economic growth and military preparedness. With China also posing a threat, Indian leaders prioritized development over conflict. In contrast, Pakistan’s economic mismanagement was exposed when catastrophic floods struck four years ago, leaving the country unable to rebuild. By then, many wealthy businessmen had already moved their assets abroad, leaving banks and financial institutions nearly empty.

Though the United States pressured the IMF to assist Pakistan, the institution encountered a nation bankrupt in both finances and governance. The Pakistani Army retained the lion’s share of resources, while civilian governments functioned as figureheads. Trade with India had long been suspended due to hostility, and food shortages plagued the population. The IMF’s proposed reforms faced resistance from both the military and the deeply entrenched religious establishment.

Over the last four decades, mullahs—through madrassas and sermons—encouraged people to prioritize Islam over national interests. This rhetoric, however, failed to address basic needs like food and employment. Disillusioned, ordinary Pakistanis now observe India’s economic progress with envy. Many silently desire normalized relations with India, reduced military spending, and an end to the decades of conflict.

However, such change is unlikely to come easily. The influence of mosques and mullahs remains strong, perpetuating the same outdated narratives. Until these barriers are addressed, Pakistan’s future will remain bleak. Hence, until the Pakistan’s civilian leadership vacuum is addressed and military is ejected, no meaningful change can take place.

Under the circumstances, the IMF has essentially thrown up its hands, emphasizing that Pakistanis must take significant steps internally before external assistance can set the country on the right path. The military refuses to relinquish its privileged status, and the same holds true for the influence of Islamic sermons, which together perpetuate a distorted image of prosperity and strength to the populace. Occasional saber-rattling against India further reinforces this illusion. Meanwhile, the wretched, impoverished masses are left with nowhere to turn.

What do you call a nation where large-scale manufacturing (LSM) has been in consistent decline for years? A strong case can be made for labeling it among the lowest of the third-world countries. This is the reality of Pakistan today. Citing data from Business Recorder of Pakistan (December 2024), the situation warrants Pakistan being described as a “begging bowl” nation.

What went wrong with a country that, at the time of its independence from Britain, showed significant promise? Pakistan boasted abundant natural resources, including fertile agricultural land fed by five rivers, perfect for an agro-industrial economy. For its first three decades, the nation experienced moderate progress. Then, in a bid to fuel confrontation with India, Pakistan’s military initiated a process of Islamization. Civilian rule was sidelined, and the military alternated between complete and partial control of the government.

A large portion of national resources, which should have been invested in development and public welfare, were instead funneled to the military. Slogans like capturing Kashmir and Jihad with the mythical Ghazwa-e-Hind—a call to conquer India—were fed to the populace. Mosques and mullahs amplified these narratives, convincing people that prosperity would follow once Pakistan achieved these territorial ambitions. The 1998 nuclear tests only emboldened this delusion, as economic priorities were neglected in favor of military expansion.

Meanwhile, India, facing the above challenges, focused on economic growth and military preparedness. With China also posing a threat, Indian leaders prioritized development over conflict. In contrast, Pakistan’s economic mismanagement was exposed when catastrophic floods struck four years ago, leaving the country unable to rebuild. By then, many wealthy businessmen had already moved their assets abroad, leaving banks and financial institutions nearly empty.

Though the United States pressured the IMF to assist Pakistan, the institution encountered a nation bankrupt in both finances and governance. The Pakistani Army retained the lion’s share of resources, while civilian governments functioned as figureheads. Trade with India had long been suspended due to hostility, and food shortages plagued the population. The IMF’s proposed reforms faced resistance from both the military and the deeply entrenched religious establishment.

Over the last four decades, mullahs—through madrassas and sermons—encouraged people to prioritize Islam over national interests. This rhetoric, however, failed to address basic needs like food and employment. Disillusioned, ordinary Pakistanis now observe India’s economic progress with envy. Many silently desire normalized relations with India, reduced military spending, and an end to the decades of conflict.

However, such change is unlikely to come easily. The influence of mosques and mullahs remains strong, perpetuating the same outdated narratives. Until these barriers are addressed, Pakistan’s future will remain bleak. Hence, until the Pakistan’s civilian leadership vacuum is addressed and military is ejected, no meaningful change can take place.

Under the circumstances, the IMF has essentially thrown up its hands, emphasizing that Pakistanis must take significant steps internally before external assistance can set the country on the right path. The military refuses to relinquish its privileged status, and the same holds true for the influence of Islamic sermons, which together perpetuate a distorted image of prosperity and strength to the populace. Occasional saber-rattling against India further reinforces this illusion. Meanwhile, the wretched, impoverished masses are left with nowhere to turn.