Why Punjab is Falling Behind Other Indian States

For over 25 years, one slogan has echoed across Punjab: “Delhi Chalo,” meaning “Let’s march to Delhi.” While often used as a rallying cry for agitation, it reflects a deeper issue. Despite Punjab’s demands, such as the creation of a Sikh-majority state, being largely met over the past six decades, some politicians continue to stoke tensions. The foreign-orchestrated Khalistani movement has caused more harm than any constructive political initiative, leaving the state mired in unrest.

Until the mid-1980s and early 1990s, Punjab was one of India’s most prosperous states, thanks to its fertile land, Bhakhra Dam, industrious workforce, and efficient grain distribution. However, its socio-economic structure is deeply stratified. Jat Sikhs, who control 80% of agricultural land, dominate farming. They also dominate the state politics and religious institutions. While other Sikhs like, Khatri Sikhs lead in commerce, and Majhbi Sikhs handle infrastructure. Meanwhile, the 38% Hindu population (other 60% are Sikh), largely passive in politics, plays a significant role in civil services and trade.

Today, Punjab struggles to reclaim its lost glory, burdened by internal divisions, mismanagement, and external interference. The long-standing leadership of Prakash Singh Badal provided stability but eventually gave way to political infighting under his successors. Rival parties, locked in power struggles, have failed to deliver on promises, leaving Punjab politically adrift.

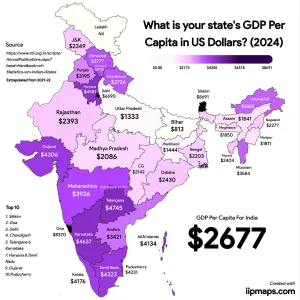

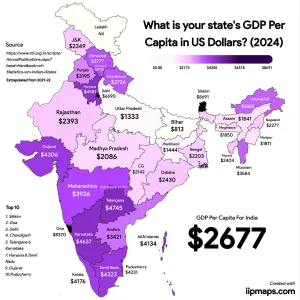

During this turmoil, Punjab missed a vital opportunity. While Prime Minister Modi’s economic reforms spurred growth across India, Punjab lacked the visionary leadership to leverage these initiatives. States like Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, and Telangana capitalized on industrialization, surpassing Punjab in prosperity. Once a leader among them, Punjab now lags behind.

Despite its advantages—an educated and hardworking labor force—Punjab has failed to attract private investment. Entrepreneurs are deterred by the state’s constant political unrest, frequent agitations, and protests for higher agricultural prices. These disruptions stall progress, sidelining Punjab in India’s economic growth story.

Punjab has immense potential for an agro-industrial revival. Instead of funneling surplus wheat and rice solely into central reserves, the state could process these into consumer products. Cotton could fuel a profitable textile industry, while underutilized land could grow fruits for distribution or value-added processing. Shifting from water-intensive rice cultivation to pulses could yield higher profits and conserve water resources. However, these initiatives remain stalled as energy is wasted on endless protests.

The state must abandon its agitation-driven mindset and focus on establishing agro-industries to boost farmers’ incomes and drive economic renewal. Only then can Punjab regain its place as a leader in India’s growth story.