A. V. Sankaran

NEARLY ten thousand years ago when mighty rivers started flowing down the Himalayan slopes, western Rajasthan was green and fertile. Great civilizations prospered in the cool amiable climate on riverbanks of northwestern India. The abundant waters of the rivers and copious rains provided ample sustenance for their farming and other activities. Some six thousand years later, Saraswati, one of the rivers of great splendour in this region, for reasons long enigmatic, dwindled and dried up. Several other rivers shifted their courses, some of their tributaries were ‘pirated’ by neigbouring rivers or severed from their main courses. The greenery of Rajasthan was lost, replaced by an arid desert where hot winds piled up dunes of sand. The flourishing civilizations vanished one by one. By geological standards, these are small-scale events; for earth, in its long 4.5 billion years history, had witnessed many such changes, some of them even accompanied by wiping out of several living species. But those that occurred in northwest India took place within the span of early human history affecting the livelihood of flourishing civilizations and driving them out to other regions.

The nemesis that overtook northwestern India’s plenty and prosperity along with the disappearance of the river Saraswati, has been a subject engaging several minds over the last hundred and fifty years. However, convincing explanations about what caused all the changes were available only in the later half of the current century through data gathered by archaeologists, geologists, geophysicists, and climatologists using a variety of techniques. They have discussed and debated their views in symposia held from time to time, many of which have also appeared in several publications. Over the last thirty years, considerable volume of literature have grown on the subject and in this article some of the salient opinions expressed by various workers are presented.

Rivers constitute the lifeline for any country and some of the world’s great civilizations (Indus Valley, Mesopotamian, and Egyptian) have all prospered on banks of river systems. Hindus consider rivers as sacred and have personified them as deities and sung their praises in their religious literature, the

Vedas (Rig,

Yajur and

Atharva), Manusmriti, Puranas and

Mahabharata. These cite names of several rivers that existed during the Vedic period and which had their origin in the Himalayas. One such river Saraswati, has been glorified in these texts and referred by various names like Markanda, Hakra, Suprabha, Kanchanakshi, Visala, Manorama etc.1,2, and

Mahabharata has exalted Saraswati River as covering the universe and having seven separate names2.

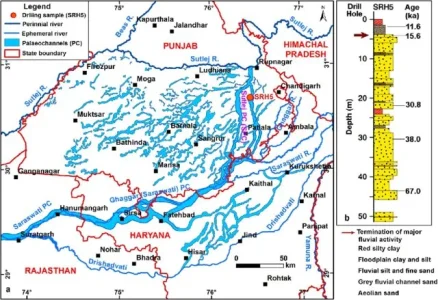

Rig veda describes it as one of seven major rivers of Vedic times, the others being, Shatadru (Sutlej), Vipasa (Beas), Askini (Chenab), Parsoni or Airavati (Ravi), Vitasta (Jhelum) and Sindhu (Indus)1,3,4<strong> </strong>(Figure 1). For full 2000 y (between 6000 and 4000 BC), Saraswati had flowed as a great river before it was obliterated in a short span of geological time through a combination of destructive natural events.

Judged in the broader perspective of geological evolution, disappearance or disintegration of rivers, shifting of their courses, capture of one river by another (river piracy), steady decline of waters culminating in drying up of their beds, are all normal responses to tectonism (uplift, faulting, subsidence, tilting), earthquakes, adverse climate and other natural events. Such catastrophic events overtook Saraswati river in quick succession, within a short geological span in the Quaternary period of the Cenozoic era (Figure 1) leading to its decline and disappearance. Similar changes to drainage of rivers have occurred during earlier geological periods also, much before human evolution. A few of the south Indian rivers like the east-flowing Pennar, Palar and Cauvery draining into the Bay of Bengal and west-flowing Swarna, Netravathi and Gurupur draining into the Arabian Sea are known to have changed their courses or got dismembered due to uplift of land. Today, their former courses or palaeochannels can be seen as dry beds5–8.

Saraswati – evolution and drainage

The river Saraswati, during its heydays, is described to be much bigger than Sindhu or the Indus River. During the Vedic period, this river had coursed through the region between modern Yamuna and Sutlej. Though Saraswati is lost, many of its contemporary rivers like Markanda, Chautang and Ghaggar have outlived it and survived till today. All the big rivers of this period –

Saraswati, Shatadru (Sutlej), Yamuna derived their waters from glaciers which had extensively covered the Himalayas during the Pleistocene times. The thawing of these glaciers during Holocene, the warm period that followed, generated many rivers, big and small, coursing down the Himalayan slopes. The melting of glaciers has also been referred in Rigvedic literature, in mythological terms, as an outcome of war between God Indra and the demon Vritra1,9. The enormity of waters available for agriculture and other occupations during those times had prompted the religiously bent ancient inhabitants to describe reverentially seven mighty rivers or ‘

Sapta Sindhu’, as divine rivers arising from slowly moving serpent (

Ahi), an apparent reference to the movement of glaciers3.

According to geological and glaciological studies11,13, Saraswati was supposed to have originated in Bandapunch masiff (Sarawati-Rupin glacier confluence at Naitwar in western Garhwal). Descending through Adibadri, Bhavanipur and Balchapur in the foothills to the plains, the river took roughly a southwesterly course, passing through the plains of Punjab, Haryana,

Rajasthan, Gujarat and finally it is believed to have debouched into the ancient Arabian Sea at the Great Rann of Kutch. In this long journey, Saraswati was believed to have had three tributaries, Shatadru (Sutlej) arising from Mount Kailas, Drishadvati from Siwalik Hills and the old Yamuna. Together, they flowed along a channel, presently identified as that of the Ghaggar river, also called Hakra River in Rajasthan and Nara in Sindh1,11 (Figure 2). The rivers, Saraswati and Ghaggar, are therefore supposed to be one and the same, though a few workers use the name Ghaggar to describe Saraswati’s upper course and Hakra to its lower course, while some others refer Saraswati of weak and declining stage, by the name Ghaggar12.

philological debate has taken place about the roots of the nomenclature ‘Saraswati’, which is referred to by the name Harkhaiti or Haravaiti (in

Avesta) in regions further west of India. The contentious point debated is whether the syllable

Ha in the river’s name changed to

Sa, later in India or

Sa to

Ha outside India. The choice of the name, Saraswati or Harkhaiti, depended upon whether one considered Aryans, the ancient inhabitants along this riverine system, as indigenous people who, upon their migration, carried the name Saraswati westwards where linguistic growth changed

Sa soon to

Ha; or, whether they were migrants from west of India who brought with them the name Harakhaiti which changed to Saraswati once they settled here2. Apart from the nomenclature, the riverine systems of the period draining northwestern India had generated considerable discussion among the scholars about the positions (hierarchy) of the other feeder rivers, big and small, their sources and causes for their shifts which affected the supply of waters to the main rivers hastening their disintegration, e.g. Saraswati and its major tributary, Drishadvati.

Hindu mythology records several legends and anecdotes that are intertwined with the river’s geologically brief existence. Every aspect of the river’s life, right from its birth to its journey down the Himalayas and over the plains towards the

Sindhu Sagara (ancient Arabian Sea), have found mention in one religious text or other, like

Rigveda, Yajurveda, Atharvaveda,

Brahmana literature, Manusmriti, Mahabharata and the

Puranas1–3. These descriptive legends have often proved helpful in cataloguing some of the natural events of the period and linking some of them with the river’s perturbations. For example, the graphic description of a war between Gods and demons detailed in one of these texts and use of fire (

Agni) in the destruction of a demon hiding in the mountains which trembled under the onslaught may possibly refer to volcanic and seismic episodes of the period2. Today, more than 8000 years since the

Vedas came into existence, some of the rivers mentioned therein have become defunct or have shifted from their original path. In the earlier years of study, their erstwhile courses were mainly inferred from archaeological evidences. These included sites of ancient settlements (some 1200 are known) of Harappan, Indus or Saraswati civilizations along river banks, the scripts and seals left behind, and references in Hindu mythology to river-bank

Ashrams and

Yagnya Kundams preserving evidences about the ritual worship practiced by the ancient inhabitants3,10–13.

Over a 3000 year-long period since the Vedic times (Figure 1), the drainage pattern of many rivers had changed much from that described in the earlier religious literature. The decline of Saraswati appears to have commenced between 5000–3000 BC, probably precipitated by a major tectonic event in the Siwalik Hills of Sirmur region. Geologic studies14 indicate destabilizing tectonic events had occurred around the beginning of Pleistocene, about 1.7 my ago in the entire Siwalik domain, extending from Potwar in Pakistan to Assam in India, resulting in massive landslides and avalanches. These disturbances, which continued intermittently, were all linked to uplift of the Himalayas. Presumably, one of these events must have severed the glacier connection and cut off the supply of glacier melt-waters to this river. As a result, Saraswati became non-perennial and dependent on monsoon rains. All its majesty and splendour of the Vedic period dwindled and with the loss of its tributaries, major and minor, Saraswati’s march to oblivion commenced around 3000 BC. Bereft of waters through separation of its tributaries15, which shifted or got captured by other neighbouring river systems, Saraswati remained here and there as disconnected pools and lakes and ultimately became reduced to a dry channel bed. Lunkaransar, Didwana and Sambhar, the Ranns of Jaisalmer, Pachpadra etc., are a few of these notable lakes, some of them highly saline today, the only proof to their freshwater descent being occurrences of gastropod shells in these lake beds16–19. With the decline and disappearance of Saraswati, the ancient civilizations, that it supported, also faded.

Inferences from geologic, remote sensing and geophysical surveys

Considerable tectonic activity connected with Himalayan orogeny continued during the Holocene and later times although uplifts to heights of 3000–4000 m were at their peak during 0.8–0.9 my span. The high elevation of the mountains perturbed the wind circulation patterns and induced climatic changes. Moderate terrain of earlier times became rugged and hilly affecting the channels of rivers14. That was the scenario of the Himalayan region when Saraswati emerged as a major river about 9000 y ago20 and flowed in all splendour during the vedic times till its decline to an impermanent monsoon dependent state some 4000 y later.

Bulk of earlier studies on Saraswati pertain more to the civilizations that flourished along its banks and many of the reasons attributed for the decline of this river were speculative. The impacts of middle to late Quaternary geologic events on the river systems in this region, however, had received only cursory attention. Awareness to the potentialities of geologic, meteorologic, climatic and other cyclic events, basically triggered by plate tectonism, earth’s orbital and tilt variations and similar global phenomena came up much later. Attempts to investigate their roles over the decline and desiccation of Saraswati began only since close of nineteenth century21–23 and gained momentum during the last three decades. Oldham23, a geologist of Geological Survey of India, was one of the first to offer as early as 1886, geological comments about Saraswati. According to him, the present dry-bed of Ghaggar River represents Saraswati’s former course and that its disappearance was precipitated when its waters were captured by Sutlej and Yamuna. This view differed from that of several others who felt that Saraswati vanished due to lack of rainfall. However, later-day meteorological research about palaeoclimates11,24–27, oxygen isotopic studies36, thermouminescenct (TL) dating28 of wind-borne and river-borne sands in the Thar desert region, radiocarbon dating of lake-bed deposits48 and archaeological evidences29,30 have all indicated that during early to middle Pleistocene period this region had enjoyed wetter climate, heavy rainfall and even recurring floods and that increase in aridity commenced by mid-Holocene (5000–3000 BC) only.

Intense investigations during the last thirty years have yielded fruitful data obtained through ground and satellite based techniques as well as from palaeoseismic, and palaeoclimatic records all of which had enabled a good reconstruction of the drainage evolution in northwestern India. In addition, TL-dating of dry-bed sands and isotopic studies of the groundwater below these channels provided useful links in these reconstruction efforts. The observed river-shifts and other changes could also be correlated with specific geologic, seismic or climatic event that occurred during the mid- to late-Quaternary period. Particularly helpful were the information gathered from LANDSAT imagery about location of former river courses in the plains and beneath the Thar desert upto the Rann of Kutch, about existence of palaeo-river valleys and identifying major structural trends (lineaments) in the region3,16,18,31–34. In spite of a large volume of such data, the chain of natural events during the Quaternary period has given rise to different interpretations about the former river courses.

Mainly, Indus and Saraswati, were the two major river systems of northwestern India during the Vedic period but the network of their tributaries, some of which are known to have deviated from their initial course or become non-existent today, have given scope for grouping these rivers into convenient classifications. Sridhar

et al.18 have classified the rivers into four main groups (Figure 2) – (i) Sindhu (Indus) and its tributaries Vitasta (Jhelum) and Askini (Chenab); (ii) Shatadru (Sutlej) and its two major tributaries Vipasa (Beas) and Parasuni or Iravati (Ravi); (iii) Saraswati and its three tributaries Markanda, Ghaggar and Patialewali, in its upper reaches and a major tributary in its middle course; (iv) Drishadvati and Lavanavati. Baldev Sahai19 grouped them into Sutlej, Ghaggar and Yamuna systems while Yash Pal and co-workers32 recognized only two major systems –

the Sutlej and the Ghaggar.

Detailed evaluation of data obtained from remote sensing, geophysical, isotopic and other studies by various workers32,33,35–40<strong> </strong>have been instrumental in sorting out many of the earlier speculative inferences and unsolved aspects of Saraswati river. Yash Pal

et al.32 have traced the palaeochannel of this river through Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan. They found that its course in these States is clearly highlighted in the LANDSAT imagery by the lush cover of vegetation thriving on the rich residual loamy soil along its earlier course. According to their findings, the river disappears abruptly in a depression in Pakistan, instead of in the sea, an observation shared by a few others also. But, digital enhancement studies35 of satellite IRS-1C data launched in 1995, combined with RADAR imagery (from European Remote Sensing satellite ERS-1/2) could identify subsurface features and thus recognize palaeochannels beneath the sands of Thar Desert. These channels are seen to extend upto Fort Abbas and Marot in Pakistan and appear in a line with present dry bed of Ghaggar (Figure 3). This river continues as Nara River in Sindh region and opens into the Rann of Kutch34. Another study33 of satellite derived data has revealed no palaeochannel link between Indus and Saraswati confirming that the two were independent rivers; also, the three palaeochannels, south of Ambala, seen to swerve westwards to join the ancient bed of Ghaggar, are inferred to be tributaries of Saraswati/ Ghaggar, and one among them, probably Drishadvati (Figure 4). The latter disappeared along with Saraswati due to shifts of its feeder streams from Siwalik and Aravalli ranges as well as due to the onset of desertification of Rajasthan15.

Geophysical surveys carried out by the Geological Survey of India to assess groundwater potential in Bikaner, Ganganagar and Jaisalmer districts in western Rajasthan desert areas have brought out several zones of fresh and less saline water in the form of arcuate shaped aquifers similar to several palaeochannels elsewhere in the State. That these subsurface palaeochannels belong to ancient rivers has been confirmed through studies37 on hydrogen, oxygen and carbon isotopes (d2H, d18O, 14C) on shallow and deep groundwater samples from these districts. The isotopic work has also indicated that there is no direct headwater connection or recharge to this groundwater from present day Himalayas. Though the antiquity of these waters and probable links to ancient rivers are thus established, the subsurface palaeochannel route beneath the desert sands obtained from hydrogeological investigations, however, differs from that derived through satellite based studies 16,35,38.

The waning period of Vedic civilization around 3700 BC was also the period that disrupted both Saraswati and Drishadvati18. Several evidences indicate that rivers of this area changed their courses often in the last 5000 y (ref. 32) and one detailed study40 about Saraswati has identified at least four progressive westward shifts in Rajasthan, due to encroaching sands. In their evaluation of the palaeochannel imagery obtained from LANDSAT, Yash Pal et al.32 observed a sudden widening of Ghaggar near Patiala which, they argue, can take place only if a major tributary had joined it. According to them, ancient Shatadru or Sutlej must have been this tributary and possibly ancient Yamuna (palaeo-Yamuna) also flowed into Ghaggar, a conclusion they claim is strengthened by archaeological findings of active life that existed at one time on their banks. During a subsequent period, Shatadru (Sutlej) swung suddenly westwards near Ropar (Figure 4) to join Indus (as also Vipas/Beas and Parasuni/Ravi, its two tributaries), deserting its earlier channel to the sea. This sudden diversion of Sutlej as well as depletion of waters from Drishadvati due to loss of its feeding streams15, appear to be major events that heralded the drying up of Saraswati. Several workers attribute this event to tectonism involving rise of Delhi-Hardwar ridge and uplift in the Aravallis11,15,16,18,32. Capture of Shatadru (Sutlej) by a tributary of Beas through headward erosion or due to diversion of Shatadru (Sutlej) through a fault are also considered as possible reasons32. Structural control over the migration of Saraswati river is also evident from studies41,42 in the Great Indian desert and adjacent parts of western Rajasthan. This area is dissected by several lineaments, some of which (e.g. Luni–Sukri lineament) were reactivated during Pleistocene–Holocene period bringing about alignment of Saraswati with Ghaggar.

Saraswati and the palaeodelta of the Great Rann

Considerable debate has taken place about Saraswati’s entry in the northern part of the Great Rann. Scholars have pointed to references in

Rigveda, Manusmriti and

Mahabharata about Saraswati disappearing in the sands at Vinäsana and not in the sea; but at the same time, there is also reference in some of these ancient texts about a narrow sea, possibly a creek, coming right upto Bikaner, but which disappeared during the Vedic times10,22. Rigvedic and archaeological references describe how Saraswati supported inland and marine trade and travel and that, around 3000 BC, there was continuous flow of this river upto even the Little Rann13.

The topography at the Great Rann is typically deltaic, developing usually at the mouth of rivers, confirming entry of a few rivers in the sea at this place. Neotectonism, reactivating faults and lineaments which are seen criss-crossing this region, as well as frequent seismicity, apart from Holocene sea-level changes all appear to have influenced development of a peculiar drainage topography in this area. The tilting and sinking of land resulting from the tectonic events have carved characteristic uplands (locally called Bets) representing areas of river mouth deposits, and lowlands which are sites of distributary channels17,28. Satellite imagery, as well as detailed mapping, have revealed network of distributaries and extensive graded deposits, products of Holocene marine regression17. It appears that Indus (Sindhu), Shatadru (Sutlej), Saraswati, Drishadvati (palaeo-Yamuna) and Lavanavati (possibly an ancestor of present day Luni river) had independent courses and opened into the Rann separately. According to Malik

et al.17, at least three rivers – proto-Shatadru (Hakra), Saraswati and Drishadvati must have drained into the Rann around 2000 BC, of which only Sindhu (Indus) has survived. The original delta complex with relict channels, including that of Nara, a continuation of Ghaggar, is today better preserved on the western side but covered by wind-borne deposits on the eastern part of the Great Rann17,43,44.

Yash Pal

et al.32 argue that though in the satellite imagery Saraswati/Ghaggar appear to debouch into the sea or a lake near Marot or Beriwala (Pakistan) (Figure 3), this place is far interior, and unlikely to be a palaeo-seacoast, even allowing for rise of sea level during the Holocene marine transgression. In fact studies about coast line changes along the west coast have shown a much lower sea level some 12,000 y back which rose to the present level only later and had remained there for the last 7000 y. These findings, therefore, discount the possibilities of a seacoast at this place45,46 though they do not rule out the river’s entry into the sea that must have existed further south of this site in those times. It may be mentioned that Quaternary neotectonism has submerged vast areas of palaeodelta complex, possibly along with palaeochannels. In this context, it is relevant to take note of the observation that Saraswati’s ancient course in this region is in continuity with another dry river bed–Hakra or Sotra which can be traced through Bikaner to Bhahawalpur and Sind in Pakistan, and finally upto the Rann of Kutch. Such a course appears likely if we backtrack the delta distributaries inland, when it is noticed they connect up with the existing palaeochannels there. Some of these are actually extensions of relict channels seen beneath the sands of Thar Desert, as found out by geophysical and hydrogeological surveys16,17,35,38.

While tectonism had certainly a major role in shaping the fate of Saraswati and other rivers, this could not have been the only agent bringing about various changes that led to its downfall. Even though the role of climate on the disappearance of Saraswati system was underestimated by some of the earlier workers, undoubtedly it must have exercised considerable sway during the Holocene, a period during which major climatic swing has been noted globally26,27,36,47. It is well known that variation in earth’s orbit and tilt of earth’s axis affect the earth’s climate (Milankovitch and albedo forces). A drastic weather change related to these phenomena had peaked around 7000 BC26. Recent studies have shown that the onset of an arid climate occurred in two pulses –

at 4700–3700 and at 2000–1700 BC26, both of which had fairly wide impact not only in India in the desertification of western Rajasthan but in