India as an Alternative to China

The idea of India serving as an alternative to China for Western manufacturing exists but faces significant hurdles. Over the past 30 years, China has achieved phenomenal progress in industrial and manufacturing capabilities, making it nearly impossible for India to match that level within a decade or so.

India’s manufacturing sector lags significantly behind China. Moreover, China holds a near-monopoly on critical raw materials, such as lithium for batteries and rare earth metals essential for military systems, consumer electronics, and renewable energy technologies etc.. With the largest known reserves of these minerals, China has solidified its dominance in high-tech industries.

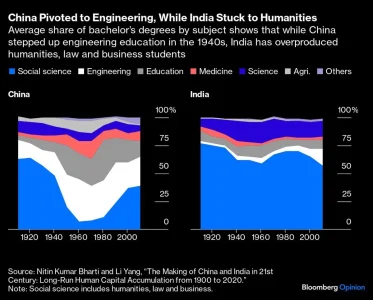

China strategically transferred consumer goods manufacturing from the West, and used export revenue to build infrastructure and more industry. It used low currency conversion rate to price its manufactured goods cheap in the international markets. Much of the products shipped out were replicate of Western technology but the West thought that it was alright as long as they got cheap products. As Chinese experience grew they ventured into high technology items, often copying the products abroad and again selling them at a lower price. Hence, Chinese progress was phenomenal for the past 20 years.

The electric vehicle (EV) industry exemplifies this approach. By acquiring expertise from Tesla’s Chinese plant, China built its own EV plants without significant R&D costs. Similarly, in electronics, China dominates as the world’s largest exporter, accounting for 33% of global exports in 2022. Its industrial base and government support make it difficult for others, including India, to compete.

Alternative India:

India remains in a nascent stage, primarily assembling imported components. For example, phones, LCD screens, LEDs, and other electronics rely heavily on Chinese imports. This dependency underscores India’s limited role in the global manufacturing value chain.

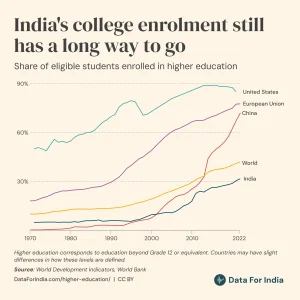

China’s dependence on exports to the West, coupled with the West’s shift away from single-source supply chains, presents a significant opportunity for India to establish itself as a key player in high-value supply chains. However, several challenges persist. The West’s deep financial investment in China—exceeding $1 trillion between 1995 and 2015—and India’s historically restrictive business regulations under its democratic framework have slowed progress. That said, the landscape is evolving. While amending laws enacted through the previous parliamentary process remains a complex and time-consuming task, reforms are underway. As a result, the West is increasingly viewing India as a viable alternative.

The notion of “Alternative India” gained traction after COVID-19 disrupted China’s supply chain, but meaningful shifts have yet to occur. Without substantial investment and policy reforms, India will struggle to attract the manufacturing base it seeks.

The only scenarios likely to disrupt China’s export dominance are war, significant trade barriers, or targeted tariffs, such as those, as media alleges, to be imposed by incoming U.S. President Trump. However, such measures risk destabilizing global supply chains, making them politically and economically unviable at the outset. But cleverly thought out plan of tariffs will do the job.

India’s rise will depend on leveraging its strengths and developing niches where it can excel. While it may never fully catch up with China, it can carve out its own space in the global economy by focusing on areas where it can compete effectively.