When Amar Faqira’s 3-year-old son abruptly lost movement in his foot last year, doctors offered little hope, and panic gripped his family.

Mr. Faqira made a vow. If his prayers were answered and the boy recovered, he would make a 200-mile pilgrimage through blistering plains and jagged terrain to the Hinglaj Devi temple, a site sacred to Hindus, a tiny minority in Pakistan.

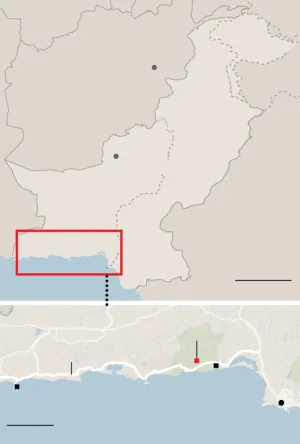

The child regained strength a year later. And true to his word, Mr. Faqira set off in late April on a seven-day walk to the temple, which is nestled deep in the rust-colored mountains of Balochistan, a remote and restive province in Pakistan’s southwest.

The goddess “heard me and healed my son,” Mr. Faqira said before the trek, as he gathered with friends and family in his neighborhood in Karachi, a metropolis on the coast of the Arabian Sea. “Why shouldn’t I fulfill my vow and endure a little pain for her joy?”

With that sense of gratitude, Mr. Faqira and two companions, wearing saffron head scarves and carrying a ceremonial flag, joined thousands of others on the grueling journey to Hinglaj Devi, where Pakistan’s largest annual Hindu festival is held.

Image

Mr. Faqira, wearing a saffron head scarf, sat with his son at home in Karachi before the pilgrimage.

Mr. Faqira carried a ceremonial flag as he walked through his neighborhood, where family and neighbors gathered to say goodbye before his departure on the pilgrimage

Mr. Faqira praying at a Hindu temple in Karachi before the pilgrimage.

Along a winding highway and sun-scorched desert paths, groups of resolute pilgrims — mostly men but also women and children — trudged beneath the unforgiving sky, in heat that reached 113 degrees Fahrenheit, or 45 degrees Celsius. Some bore idols of the deity associated with the temple. All chanted

“Jai Mata Di,

” a call meaning “Hail the Mother Goddess.”

The pilgrimage is an act of spiritual devotion and cultural preservation. Pakistan’s Hindus number about 4.4 million and make up less than 2 percent of the country’s population, which is more than 96 percent Muslim. Hindus are often treated as second-class citizens, systemically discriminated against in housing, jobs and access to government welfare.

For many, the pilgrimage to Hinglaj Devi is comparable in significance to the

hajj in Islam, a once-in-a-lifetime obligation of faith. The yearning to make the journey is also strong among Hindus in India, especially in the states of Gujarat and Rajasthan, though it has long been very difficult for Indians to receive visas to travel to Pakistan. Those states, which border Pakistan, have deep spiritual links to Hinglaj Devi that are rooted in traditions predating

the 1947 partition that divided the two countries.

www.cnbctv18.com