The Fall of Assad in Syria: High Risks for U.S. Regime Change Policies

Two regimes particularly disfavored by the United States have fallen in Asia and the Middle East in last four months. One was the elected government of Sheikh Hasina in Bangladesh, and the other, the dictatorial regime of Bashar al-Assad in Syria. Both were abruptly overthrown by Islamist forces. While I have extensively covered the fall of Sheikh Hasina in earlier posts, I will focus here on the Assad regime’s collapse, which spanned five decades under the leadership of both Hafez and Bashar al-Assad.

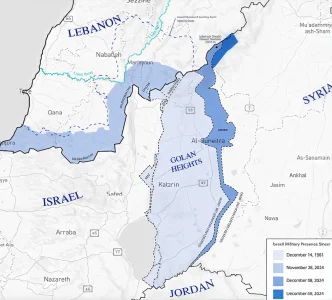

The Assad regime fell with startling speed, leaving little opportunity for Bashar al-Assad to reform his rule. The turning point came on December 8, 2024, when Assad quietly fled his palace and sought refuge in Russia. This followed the rapid advance of rebel forces, who had captured Aleppo—a key city in northern Syria—before pushing toward Damascus.

The rebels’ success was not achieved in isolation; external support played a decisive role. The U.S. had expressed its desire to see Assad step down as early as 2011, when then-President Obama urged him to relinquish power. Washington’s initial involvement in Syria stemmed from efforts to counter the rise of ISIS amidst the country’s ongoing civil war. Despite its struggles to establish political stability in Iraq following the Gulf Wars, the U.S. sought to preempt the emergence of groups like Al-Qaeda in neighboring Syria. However, as the rebels’ advance gained momentum, defections among Assad’s ministers accelerated his downfall.

Emerging reports indicate that Turkey was a crucial supporter of the rebels, providing logistical assistance that enabled their swift advance. This external backing underscores the complex regional dynamics that shaped Assad’s fall and highlights the broader risks inherent in U.S. regime change policies. In all this happening, it is not difficult to conclude that U.S. via Turkey had major involvement.

Who Are the Rebels?

The rebels are led by Ahmed Al-Sharaa, also known as Abu Mohammad al-Jolani, who heads the designated terrorist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). Al-Sharaa has longstanding ties to both Al-Qaeda and ISIS. The U.S. initially placed a $10 million bounty on his head, signaling its disapproval of his activities. However, faced with the choice between retaining Bashar al-Assad or supporting Al-Sharaa, the U.S. appeared to shift its stance. The bounty on Al-Sharaa was quietly lifted, effectively signaling a preference for him.

But, is U.S. support for an Islamist leader like Al-Sharaa a prudent move? History suggests this decision could backfire. HTS may currently show a willingness to stabilize Syria, but Islamist groups tend to adhere to their ideological roots regardless of time or context. This “temporary truce” to facilitate governance might unravel, and there may have been no viable alternative.

The fall of Assad has clear geopolitical ramifications. Russia emerges as one of the main losers, as its influence in Syria diminishes with Assad’s removal. Similarly, Iran, a key backer of the Assad regime, is seeing its regional influence wane, likely marking the end of its dominance in Syria.

On the other hand, Israel gains a strategic advantage. Its recent extensive bombing campaign in Syria has disrupted supply routes to Hezbollah and Hamas that relied heavily on Syrian territory.

As for how Islamist rule in Syria will unfold, the future remains uncertain. What is clear is that the U.S. is unlikely to find favor with HTS in the long term. This raises concerns that, sooner or later, these Islamists may turn against U.S.