When we recall the famous quote that history is just an agglomeration of the biographies of eminent people, the statement needs to be quantified so that we can get a true picture of the

moral and the

ethical aspects of history. Indeed there is no better yardstick to judge the national character of a country than the kind of people it regards as heroes. Because he is relatively contemporary, how would we judge Germany if it continued to regard Adolf Hitler as a hero? On the contrary, the fact that he is still considered a national shame and a taboo also throws equal light on the national character of Germany.

When we apply the same principle for example, to Pakistan and innumerable mosques in the Bharatavarsha that has survived, who are celebrated as heroes in these realms? Muhammad bin Qasim, Mahmud of Ghazni, Muhammad Ghori, Timur, Babar, Aurangzeb and Tipu. The striking feature common to all these "heroes" is the fact that not only did they did

not build anything of value but savagely annihilated painstaking works of lasting value, built over centuries.

Magnitude of the Loss

Therefore, when we study the forgotten Hindu history of Pakistan, what are the kind of people we encounter? A short list suffices. Maharshi Panini, Acharya Chanakya, Ashvaghosha, Nagasena (author of the famous

Milindapanha), Vasubandhu, Jivaka (Gautama Buddha’s physician), and Charaka. These were civilisation-builders and not merely eminent people who had attained excellence in their respective domains. It is beyond the scope of this series to elaborate their contributions to the Sanatana culture and civilisation.

But on a larger point, for centuries on end, the Afghanistan-Pakistan region --i.e., the Northwestern region--was a great centre of Sama Veda and Atharva Veda learning. So when we say Northwestern, we also ask: north west of what? The obvious answer: northwest of Bharatavarsha. Today, only one branch of the Atharva Veda remains in the remaining area of Bharatavarsha. All the other eight branches have vanished because they had been preserved in this region. Equally, the Jaimini branch of the Sama Veda was preserved in Sindh and Gujarat. According to some estimates, there were about

one thousand branches of the Sama Veda – only

three have survived today.

Indeed, for centuries, the Sindh and the Northwestern region had vibrant contact with Kashmir, which was looked upon as the land blessed by Saraswati herself. Kashmir's enduring fame as one of the greatest centres of Sanskrit is too well-known to be repeated. Fragments of the surviving literature and other artefacts from the original Sindh mention many poets, writers and scholars hailing from Kashmir. However, almost no literary work composed in (the original) Sindh itself survives today. But from just what is available, we get a huge list of

five hundred-plus scholars, poets, etc of the highest standard who lived and flourished in Sindh. Scores of Dharmashastras and other legal treatises were composed in this region but

we don't have any record of them whatsoever.

Think about it. Maharshi Panini didn’t just write his magnificent grammar, the

Asthadhyayi, overnight. He toiled patiently and diligently built upon a long and ancient

Parampara or tradition. He also mentions a big list of geographical locations of ancient India. A measure of the perennial nature of his foundational work can be had in the countless praise that British researchers heaped upon him. For example, Alexander Cunningham's superb work on the ancient and medieval geography of India mentions in so many words that Panini was both inevitable and indispensable for any work on ancient India. Yet we have Romila Thapar and her gang which casually dismisses Panini with an arrogance that's truly incredible.

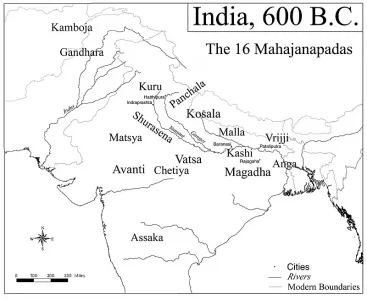

Maharshi Panini divides the geography of Bharatavarsha into two major categories: all places to the east of the Sindhu River and to the west of it. Needless, the names of the majority of places on this other side of the Sindhu are gone forever, replaced by unpronounceable names.

Lahore for example, was a great and renowned centre of Sanskrit learning even during the pre-independence period. One of the legendary Sanskrit scholars and a Jnanapith Awardee, Padmabhushan, Vidyavachaspati, Professor Satyavrat Sastri's antecedents are from Lahore.

It might sound unbelievable now, but even in the early years of independence, the Arya Samaj had made Lahore as one of its more powerful and active hubs.

Shiva Murti Artefact from the Pala Period

Even if we claim--as numerous Hindus do--that all these are ancient histories and we should "move on" and focus on the "present" and the "future," here is a fairly contemporary account. Of the fate of Kashmir. Until Article 370 was scrapped, this was the story of Kashmir: a no-holds-barred civilisational assault lasting for nearly a century. Remember that Kashmir was not part of the India that was lost in 1947 to Pakistan. The question that logically arises is this: why did Hindus lose it? The answer is the same...the same narrative that continues to play out on the streets of Delhi even as I write this: because the Muslim leadership of that period felt unsafe in a country where Hindus were majority.

Think about the Hindu temples in Kashmir over the last seventy-plus years. Where are these temples in Kashmir today? What about the fate of those temples that were left unmolested? Why aren't new temples getting built there? Why and how does the sacred Shankaracharya Hill acquire an abomination called Takht-e-Suleiman? The underlying point in all such questions is really simple: if Hindus cannot--or are not allowed to--perform something as fundamental as Puja, they're destroyed in ways our imagination cannot even fathom.

Pakistan is only as recent as 70 years, less than a drop in the ocean of time. And the memory of its Hindu past is almost completely erased.