Costs have soared and completion has been pushed back to 2031 as India and Japan disagree over signalling and the cost of rolling stock. Srinand Jha reports.

March 14, 2025

THE latest revised cost of building India’s first high-speed line, running for 508km from Mumbai to Ahmedabad, is understood to have risen to Rs 2 trillion ($US 24.3bn) and the timeline for completion extended to 2031.

The original cost estimate for the project was Rs 960bn and the target completion date fixed for 2024. The cost was revised upwards to Rs 1.08 trillion following the decision to build the new line on viaduct due to poor ground conditions on sections of the route, including near Bharuch and Baroda in Gujarat state.

The National High Speed Rail Corporation (NHSRCL) that is delivering the project recently informed the Railway Board that costs have increased due to a range of factors, including slow progress during the Covid-19 pandemic and the fluctuating exchange rate between the Rupee and the Yen.

Internal estimates prepared by Indian Railways (IR) suggest that delays have caused losses to escalate by 5% compared with the project cost. On this basis, building the high-speed line is likely to produce a loss of Rs 100bn a year.

NHSRCL’s official position is that the cost of the project and the timeline for delivering it cannot be determined at this point. In a report published on March 10 by the Indian Parliament’s Standing Committee on Railways, IR officials are quoted as saying: “Timelines and costs can only be ascertained after finalisation of all contract packages, completion of all associated work timelines related to civil structures, track, electric power supply, signalling and telecommunications, and the supply of rolling stock.”

Civil works on the project have progressed rapidly, with overall physical progress standing at 48.55% in January for expenditure of Rs 711.16bn. The main cause of delay at present is the failure to decide on two key issues: the type of rolling stock and the signalling system to be deployed on the new line.

On the understanding that Japanese technology will be used, 80% of the project cost is being funded by a 50-year loan from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (Jica), bearing interest at 0.1% and with a 20-year moratorium on repayment. Of the remainder, 50% will be provided by the Indian government and 50% by the states of Maharashtra and Gujarat.

At a recent meeting of the inter-ministerial group overseeing the project, the Japanese delegation is understood to have informed its Indian counterparts that it would not be possible to deliver Shinkansen high-speed trains before 2030, as India has yet to order them. A total of 400 cars are needed to operate as eight and 16-car trains.

India has been attempting to persuade Japan to reduce its price of Rs 200bn for the new trains, but so far without success. Within the Ministry of Railways, it is felt in some quarters that high-speed trains could be procured from European manufacturers at approximately half the cost. However, this could prove problematic for India, as integrating European rolling stock with Japanese signalling technology is unlikely to provide the best solution.

The Indian government would also need to pay upfront for new trains from Alstom or Siemens, whereas the Japanese trains will be funded by the soft loan from Jica, repayable in 50 years. In addition to training for high-speed operations, Indian engineers are already preparing to work on domestic production of Shinkansen components in the long term, while the agreement between India and Japan specifies that at least 50% of components will be procured from Japanese companies.

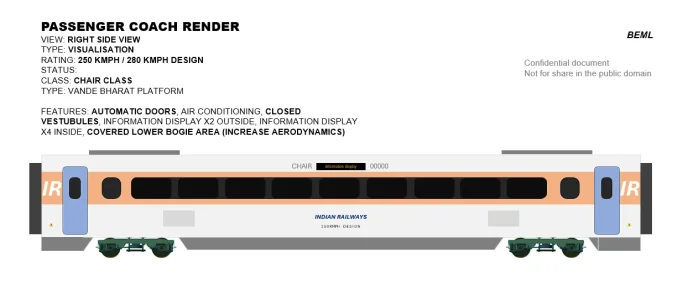

In what appears as an attempt by India to pressure Japan to reduce the price of the new high-speed fleet, IR subsidiary Integral Coach Factory (ICF) awarded a Rs 8.7bn contract in October to the state-owned Bharat Earth Movers (BEML) to supply two trains with a maximum speed of 280km/h.

Depending on the success of the two prototypes, these domestically-designed trains will be deployed on India’s first high-speed line. BEML will partner with Medha Servo Drives, which developed the traction system of IR’s Vande Bharat EMU, and is reported to have appointed EC Engineering of Poland as engineering design consultant. It is expected that other electrical systems and onboard signalling equipment will be supplied by Siemens.

The BEML trains could serve as a stop-gap in order to conduct trials on the 50km Surat - Bilimoria section, or potentially operate over the entire 508km high-speed line at an average speed of around 180km/h. However, BEML is understood to have informed IR that it will not be possible for deliveries to start before 2028, meaning that passenger services on the Mumbai - Ahmedabad high-speed line are unlikely to begin before 2029, even at a lower speed.

Japan and India have also been unable to reach agreement on the signalling system for the new line.

Japan has insisted on the leaky feeder or radiating cable technology used on Shinkansen lines, while the Indian government has been contemplating the use of ETCS Level 2.

The latter, developed in Europe, is now in operation in India on the Regional Rapid Transit System (RRTS) commuter line in Delhi, and the contract awarded to BEML includes provision to install ETCS Level 2 on the new 280km/h trains.

Japan and India may have reached an impasse for the time being, but the silver lining is that neither of the two countries can walk away from the deal. It is therefore possible and likely that a middle way will be found to resolve these contentious issues.

The cost of building the high-speed line from Mumbai to Ahmedabad has risen to $US 24.3bn and the timeline for completion extended to 2031.

www.railjournal.com