Geopolitical Tensions over China’s Mega Dam on the Brahmaputra

Is it a folly or simply over-engineering?

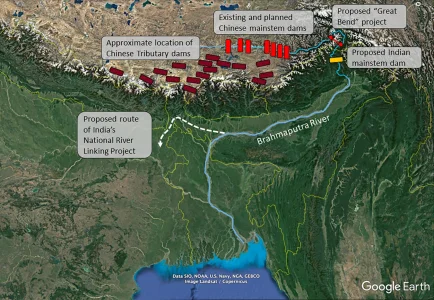

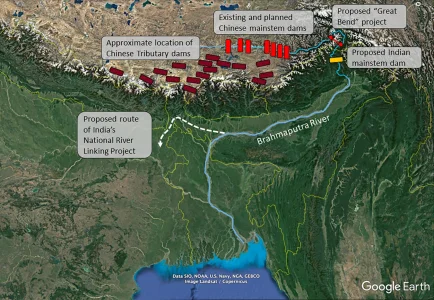

China, known for its strategic maneuvering, is attempting construction of a mega dam, valued between $100 billion on a bend of the Brahmaputra River in Tibet, near the Indian border. The Brahmaputra, a river fed primarily by glacier melt, runs along the northern side of the Himalayas at an elevation of 4,000 to 3,000 meters. Since the Tibetan Plateau sees little rainfall, the river’s flow in this region is mostly a snowmelt. Researchers estimate that only 25 to 33% of the river’s flow in the Assam plains originates in Tibet, while the remaining 65% comes from rainfall in Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Assam, and surrounding regions. Initially, one might think the dam poses little threat, particularly as it is an inflow dam, with no water is diverted, however, yet concerns rise during the dry season, when the river’s discharge naturally decreases. Moreover, if there is not much flow in the river then Chinese are planning to use water head (difference in elevation) to generate massive amount of electricity. Without enough hydrological data, my guess is that head alone cannot generate that amount of electricity (60 GigaWatts).

China’s ambition to build this dam in such a hazardous location—an earthquake-prone river bend where the river drops 2,500 meters—raises serious questions. The area is highly vulnerable to landslides and other natural disasters. China’s confidence seems rooted in two factors: the availability of labor following the failure of housing projects and failed Belt and Road Initiatives.

The Brahmaputra Dam would be an unprecedented engineering challenge, as the river flows through the world’s deepest known canyon at the bend. China’s plan is to harness the steep 2,500-meter drop to generate power—three times the capacity of the Three Gorges Dam—by constructing three 35-kilometer tunnels beneath the Himalayan slopes. These tunnels would bypass the river’s natural curve, funneling water to turbines on the other side. To feed the turbines, China would build a massive reservoir to store water and release it through the tunnels. However, the region’s geological instability, compounded by the weight of billions of tons of water, could trigger earthquakes, creating a significant risk. Despite these concerns, China appears undeterred.

Why is India Concerned?

China’s construction of the Brahmaputra dam could elevate it to the status of an “upstream superpower,” giving it control over the water supply to downstream nations like India and Bangladesh. Without a formal water-sharing agreement or basin-wide management system, China’s intentions remain suspect. Although earlier reports suggested that China aimed to divert water to its dry regions 3,000 km away, this does not seem to be the case today. Nevertheless, China’s long-term motives are always a suspect.

Another major Indian concern is the potential impact on farming in the Assam plains. The fast-flowing Brahmaputra deposits nutrient-rich soil in these plains, supporting agriculture. A dam would disrupt this natural process. Additionally, the dam could face its own challenges, with sediment building up in the reservoir and potentially blocking the tunnels. That is China’s problem.

Bangladesh, the other downstream country, appears less vocal on the issue. Given its close ties with China, Bangladesh might prefer to look the other way, minimizing any public concerns.

One significant risk is the possibility that China could deliberately release large amounts of water during the rainy season, potentially flooding the Assam plains. To counter this threat, India plans to build an $8 billion dam in Arunachal Pradesh, which would store excess water and release it during the dry season—a promising idea. Additionally, Chinese dam could also complicate India’s plans to link the Brahmaputra with other rivers via the Siliguri Corridor, an idea that has not yet been seriously considered. During any future negotiations over a basin-wide agreement, this project should be addressed and agreed upon. What it means is that when India speaks, China has to listen. Those previous days of Chinese domination are over.}